Getting Started

Without the right tools, crawling and scraping the web can be difficult. At the very least, you need an HTTP client to make the necessary requests, but that only gets you raw HTML and sometimes not even that. Then you have to read this HTML and extract the data you're interested in. Once extracted, it must be stored in a machine-readable format and easily accessible for further processing, because it is the processed data that holds value.

Apify SDK covers the process end-to-end. From crawling the web for links and scraping the raw data to storing it in various machine readable formats, ready for processing. With this guide in hand, you should have your own data extraction solutions up and running in a few hours.

Intro

The goal of this getting started guide is to provide a step-by-step introduction to all the features of the Apify SDK. It will walk you through creating the simplest of crawlers that only prints text to console, all the way up to complex systems that crawl pages, interact with them as if a real user were sitting in front of a real browser and output structured data.

Since Apify SDK is usable both locally on any computer and on the Apify platform, you will be able to use the source code in both environments interchangeably. Nevertheless, some initial setup is still required, so choose your preferred starting environment and let's get into it.

Setting up locally

To run Apify SDK on your own computer, you need to meet the following pre-requisites first:

- Have Node.js version 15.10 or higher installed.

- Visit Node.js website to download or use fnm

- Have NPM installed.

- NPM comes bundled with Node.js so you should already have it. If not, reinstall Node.js.

If you're not certain, confirm the prerequisites by running:

node -v

npm -v

Creating a new project

The fastest and best way to create new projects with the Apify SDK is to use our own Apify CLI. This command line tool allows you to create, run and manage Apify projects with ease, including their deployment to the Apify platform if you wish to run them in the cloud after developing them locally.

Let's install the Apify CLI with the following command:

npm install -g apify-cli

Once the installation finishes, all you need to do to set up an Apify SDK project is to run:

apify create my-new-project

A prompt will be shown, asking you to choose a template. Disregard the different options for now and choose the template labeled Hello world. The

command will now create a new directory in your current working directory, called my-new-project, create a package.json in this folder and install

all the necessary dependencies. It will also add example source code that you can immediately run.

Let's try that!

cd my-new-project

apify run -p

The

-pflag is great to remember, because it stands for--purgeand it clears out your persistent storages before starting the actor.INPUT.jsonand named storages are kept. Whenever you're just restarting your actor and you're not interested in the data of the previous run, you should useapify run -pto prevent the old state from messing with your current run. If this is confusing, don't worry. You'll learn about storages andINPUT.jsonsoon.

You should start seeing log messages in the terminal as the system boots up and after a second, a Chromium browser window should pop up. In the

window, you'll see quickly changing pages and back in the terminal, you should see the titles (contents of the <title> HTML tags) of the pages

printed.

You can always terminate the crawl with a keypress in the terminal:

CTRL+C

Did you see all that? If you did, congratulations! You're ready to go!

Setting up on the Apify Platform

Maybe you don't have Node.js installed and don't want the hassle. Or you can't install anything on your computer because you're using one provided by your company. Or perhaps you'd just prefer to start working in the cloud right away. Well, no worries, we've got you covered.

The Apify platform is the foundational product of Apify. It's a serverless cloud computing platform, specifically designed for any web automation jobs, that may include crawling and scraping, but really works amazingly for any batch jobs and long-running tasks.

It comes with a free account, so let's go to our sign-up page and create one, if you haven't already. Don't forget to verify your email. Without it, you won't be able to run any projects.

Once you're in, you might be prompted by our in-app help to walk through a step-by-step guide to some of our new features. Feel free to finish that, if you'd like, but once you're done, click on the Actors tab in the left menu. To read more about Actors, see: What is an actor

Creating a new project

In the page that shows after clicking on Actors in the left menu, choose Create new. Give it a name in the form that opens, let's say,

my-new-actor. Disregard all the available options for now and save your changes.

Now click on the Sources tab at the top. Disregard the version and environment variables inputs for now and proceed directly to Source code. This is where you develop the actor, if you choose not to do it locally. Just press Run below the Source code panel. It will automatically build and run the example source code. You should start seeing log messages that represent the build and after the build is complete, the log messages of the running actor. Feel free to check out the other Run tabs, such as Info, where you can find useful information about the run, or Key-value-store, where the actor's INPUT and OUTPUT are stored.

Good job. You're now ready to run your own source code on the Apify Platform. For more information, visit the Actor documentation page, where you'll find everything about the platform's various options.

First crawler

Whether you've chosen to develop locally or in the cloud, it's time to start writing some actual source code. But before we do, let's just briefly introduce all the Apify SDK classes necessary to make it happen.

The general idea

There are 4 crawler classes available for use in the Apify SDK. BasicCrawler, CheerioCrawler, PuppeteerCrawler and PlaywrightCrawler. We'll talk about their differences later. Now, let's talk about what they have in common.

The general idea of each crawler is to go to a web page, open it, do some stuff there, save some results and continue to the next page, until it's done its job. So the crawler always needs to find answers to two questions: Where should I go? and What should I do there? Answering those two questions is the only setup mandatory for running the crawlers.

The Where - Request, RequestList and RequestQueue

All crawlers use instances of the Request class to determine where they need to go. Each request may hold a lot of information,

but at the very least, it must hold a URL - a web page to open. But having only one URL would not make sense for crawling. We need to either have a

pre-existing list of our own URLs that we wish to visit, perhaps a thousand, or a million, or we need to build this list dynamically as we crawl,

adding more and more URLs to the list as we progress.

A representation of the pre-existing list is an instance of the RequestList class. It is a static, immutable list of URLs and

other metadata (see the Request object) that the crawler will visit, one by one, retrying whenever an error occurs, until there

are no more Requests to process.

RequestQueue on the other hand, represents a dynamic queue of Requests. One that can be updated at runtime by adding more

pages - Requests to process. This allows the crawler to open one page, extract interesting URLs, such as links to other pages on the same domain,

add them to the queue (called enqueuing) and repeat this process to build a queue of tens of thousands or more URLs while knowing only a single one

at the beginning.

RequestList and RequestQueue are essential for the crawler's operation. There is no other way to supply Requests = "pages to crawl" to the

crawlers. At least one of them always needs to be provided while setting up. You can also use both at the same time, if you wish.

The What - handlePageFunction

The handlePageFunction is the brain of the crawler. It tells it what to do at each and every page it visits. Generally it handles extraction of data

from the page, processing the data, saving it, calling APIs, doing calculations and whatever else you need it to do.

The handlePageFunction is provided by you, the user, and invoked automatically by the crawler for each Request from either the RequestList or

RequestQueue. It always receives a single argument and that is a plain Object. Its properties change depending on the crawler class used, but it

always includes at least the request property, which represents the currently crawled Request instance (i.e. the URL the crawler is visiting and

related metadata) and the autoscaledPool property, which is an instance of the AutoscaledPool class and we'll talk about

it in detail later.

// The object received as a single argument by the handlePageFunction

{

request: Request,

autoscaledPool: AutoscaledPool

}

Putting it all together

Enough theory! Let's put some of those hard-learned facts into practice. We learned above that we need Requests and a handlePageFunction to setup

a crawler. We will also use the Apify.main() function. It's not mandatory, but it makes our life easier. We'll

learn about it in detail later on.

Let's start with something super easy. Visit a page, get its title and close. First of all we need to require Apify, to make all of its features available to us:

const Apify = require('apify');

Easy, right? It really doesn't get much more difficult than that. For the purposes of this tutorial, we'll be scraping our own webpage

https://apify.com. Now, to get there, we need a Request with the page's URL in one of our sources,

RequestList or RequestQueue. Let's go with RequestQueue for now.

const Apify = require('apify');

// This is how you use the Apify.main() function.

Apify.main(async () => {

// First we create the request queue instance.

const requestQueue = await Apify.openRequestQueue();

// And then we add a request to it.

await requestQueue.addRequest({ url: 'https://apify.com' });

});

If you're not familiar with the

asyncandawaitkeywords used in the example, you should know that these are native syntax in modern JavaScript. You can learn more about them here.

The requestQueue.addRequest() function automatically converts the plain object we passed to it to a

Request instance, so now we have a requestQueue that holds one request which points to https://apify.com. Now we need the

handlePageFunction.

// We'll define the function separately so it's more obvious.

const handlePageFunction = async ({ request, $ }) => {

// This should look familiar if you ever worked with jQuery.

// We're just getting the text content of the <title> HTML element.

const title = $('title').text();

console.log(`The title of "${request.url}" is: ${title}.`);

};

Wait, where did the $ come from? Remember what we learned about the handlePageFunction earlier. It expects a plain Object as an argument that

will always have a request property, but it will also have other properties, depending on the chosen crawler class. Well, $ is a property provided

by the CheerioCrawler class, which we'll set up right now.

const Apify = require('apify');

Apify.main(async () => {

const requestQueue = await Apify.openRequestQueue();

await requestQueue.addRequest({ url: 'https://apify.com' });

const handlePageFunction = async ({ request, $ }) => {

const title = $('title').text();

console.log(`The title of "${request.url}" is: ${title}.`);

};

// Set up the crawler, passing a single options object as an argument.

const crawler = new Apify.CheerioCrawler({

requestQueue,

handlePageFunction,

});

await crawler.run();

});

And we're done! You just created your first crawler from scratch. It will download the HTML of https://apify.com, find the <title> element, get

its text content and print it to console. Good job!

To run the code locally, copy and paste the code, if you haven't already typed it in yourself, to the main.js file in the my-new-project we

created earlier and run apify run from that project's directory.

To run the code on Apify Platform, just replace the original example with your new code and hit Run.

Whichever environment you choose, you should see the message

The title of "https://apify.com" is: Web Scraping, Data Extraction and Automation - Apify. printed to the screen. If you do, congratulations and

let's move onto some bigger challenges! And if you feel like you don't really know what just happened there, no worries, it will all become clear when

you learn more about CheerioCrawler.

CheerioCrawler aka jQuery crawler

This is the crawler that we used in our earlier example. Our simplest and also the fastest crawling solution. If you're familiar with jQuery, you'll

understand CheerioCrawler in minutes. Cheerio is

essentially jQuery for Node.js. It offers the same API, including the familiar $ object. You can use it, as you would jQuery, for manipulating

the DOM of a HTML page. In crawling, you'll mostly use it to select the right elements and extract their text values - the data you're interested in.

But jQuery runs in a browser and attaches directly to the browser's DOM. Where does cheerio get its HTML? This is where the Crawler part of

CheerioCrawler comes in.

Overview

CheerioCrawler crawls by making plain HTTP requests to the provided URLs. As you remember from the previous section, the

URLs are fed to the crawler using either the RequestList or the RequestQueue. The HTTP responses

it gets back are HTML pages, the same pages you would get in your browser when you first load a URL.

Note, however, that modern web pages often do not serve all of their content in the first HTML response, but rather the first HTML contains links to other resources such as CSS and JavaScript that get downloaded afterwards and together they create the final page. See our

PuppeteerCrawlerto crawl those.

Once the page's HTML is retrieved, the crawler will pass it to Cheerio for

parsing. The result is the typical $ function, which should be familiar to jQuery users. You can use this $ to do all sorts of lookups and

manipulation of the page's HTML, but in scraping, we will mostly use it to find specific HTML elements and extract their data.

Example use of Cheerio and its $ function in comparison to browser JavaScript:

// Return the text content of the <title> element.

document.querySelector('title').textContent; // plain JS

$('title').text(); // Cheerio

// Return an array of all 'href' links on the page.

Array.from(document.querySelectorAll('[href]')).map((el) => el.href); // plain JS

$('[href]')

.map((i, el) => $(el).attr('href'))

.get(); // Cheerio

This is not to show that Cheerio is better than plain browser JavaScript. Some might actually prefer the more expressive way plain JS provides. Unfortunately, the browser JavaScript methods are not available in Node.js, so Cheerio is our best bet to do the parsing.

When to use CheerioCrawler

Even though using CheerioCrawler is extremely easy, it probably will not be your first choice for most kinds of crawling or scraping in production

environments. Since most websites nowadays use modern JavaScript to create rich, responsive and data-driven user experiences, the plain HTTP requests

the crawler uses may just fall short of your needs.

But CheerioCrawler is far from useless! It really shines when you need to cope with extremely high workloads. With just 4 GBs of memory and a single CPU

core, you can scrape 500 or more pages a minute! (assuming each page contains approximately 400KB of HTML) To scrape this fast with a full browser

scraper, such as the PuppeteerCrawler, you'd need significantly more computing power.

Advantages:

- Extremely fast

- Easy to set up

- Familiar for jQuery users

- Super cheap to run

- Each request can go through a different proxy

Disadvantages:

- Does not work for all websites

- May easily overload the target website with requests

- Does not enable any manipulation of the website before scraping

Basic use of CheerioCrawler

Now that we have an idea of the crawler's inner workings, let's build one. We'll use the example from the previous section and improve on it by

letting it truly crawl the page, finding new links as it goes, enqueuing them into the RequestQueue and then scraping them.

Refresher

Just to refresh your memory, in the previous section we built a very simple crawler that downloads the HTML of a single page, reads its title and prints it to the console. This is the original source code:

const Apify = require('apify');

Apify.main(async () => {

const requestQueue = await Apify.openRequestQueue();

await requestQueue.addRequest({ url: 'https://apify.com' });

const handlePageFunction = async ({ request, $ }) => {

const title = $('title').text();

console.log(`The title of "${request.url}" is: ${title}.`);

};

// Set up the crawler, passing a single options object as an argument.

const crawler = new Apify.CheerioCrawler({

requestQueue,

handlePageFunction,

});

await crawler.run();

});

Earlier we said that we would let the crawler:

- Find new links on the page

- Filter only those pointing to the same hostname, in this case

apify.com - Enqueue them to the

RequestQueue - Scrape the newly enqueued links

So let's get to it!

Finding new links

There are numerous approaches to finding links to follow when crawling the web. For our purposes, we will be looking for <a> elements that contain

the href attribute. For example <a href="https://apify.com/store">This is a link to Apify Store</a>. To do this, we need to update our Cheerio

function.

const links = $('a[href]')

.map((i, el) => $(el).attr('href'))

.get();

Our new function finds all the <a> elements that contain the href attribute and extracts the attributes into an array of strings. But there's a problem. There could be relative links in the list and those can't be used on their own. We need to resolve them using our domain as base URL and

we will use one of Node.js' standard libraries to do this.

Apify exposes two URL properties: request.url and request.loadedUrl. What's the difference? Well, request.url is the URL of the first request. In case of redirects, the URL changes. The final one is stored as request.loadedUrl.

// At the top of the file:

const { URL } = require('url');

// ...

const { hostname } = new URL(request.loadedUrl);

const absoluteUrls = links.map((link) => new URL(link, request.loadedUrl));

Filtering links to same domain

Websites typically contain a lot of links that lead away from the original page. This is normal, but when crawling a website, we usually want to crawl that one site and not let our crawler wander away to Google, Facebook and Twitter. Therefore, we need to filter out the off-domain links and only keep the ones that lead to the same domain.

Don't worry, we'll learn how to do this with a single function call using Apify in a few moments.

// At the top of the file:

const { URL } = require('url');

// ...

const links = $('a[href]')

.map((i, el) => $(el).attr('href'))

.get();

const { hostname } = new URL(request.loadedUrl);

const absoluteUrls = links.map((link) => new URL(link, request.loadedUrl));

const sameDomainLinks = absoluteUrls.filter((url) =>

url.hostname.endsWith(hostname),

);

// ...

This includes subdomains. In order to filter the same origin, simply compare the url.origin property instead:

const { origin } = new URL(request.loadedUrl);

const absoluteUrls = links.map((link) => new URL(link, request.loadedUrl));

const sameDomainLinks = absoluteUrls.filter((url) => url.origin === origin);

The

URLclass contains many other useful properties. You can read more abouturl.originhere.

Enqueueing links to RequestQueue

This should be easy, because we already did that earlier, remember? Just call requestQueue.addRequest() for all the new

links. This will add them to the end of the queue for processing.

// At the top of the file:

const { URL } = require('url');

// ...

const links = $('a[href]')

.map((i, el) => $(el).attr('href'))

.get();

const { origin } = new URL(request.loadedUrl);

const absoluteUrls = links.map((link) => new URL(link, request.loadedUrl));

const sameDomainLinks = absoluteUrls.filter((url) => url.origin === origin);

// Add the requests in series. There's of course room for speed

// improvement by parallelization. Try to implement it, if you wish.

console.log(`Enqueueing ${sameDomainLinks.length} URLs.`);

for (const url of sameDomainLinks) {

await requestQueue.addRequest({ url: url.href });

}

// ...

Scrape the newly enqueued links

And we're approching the finishing line. All we need to do now is integrate the new code into our original crawler. It will be easy, because

almost everything needs to go into the handlePageFunction. But just before we do that, let's introduce the first crawler configuration option that

is not a handlePageFunction or requestQueue. It's called maxRequestsPerCrawl.

The maxRequestsPerCrawl limit

This configuration option is available in all crawler classes and you can use it to limit the number of Requests the crawler should process. It's

very useful when you're just testing your code or when your crawler could potentially crawl millions of pages and you want to save resources. You can

add it to the crawler options like this:

const crawler = new Apify.CheerioCrawler({

maxRequestsPerCrawl: 20,

requestQueue,

handlePageFunction,

});

This limits the number of successfully handled Requests to 20. Bear in mind that the actual number of processed requests might be a little higher

and that's because usually there are multiple Requests processed at the same time and once the 20th Request finishes, the other running Requests

will be allowed to finish too.

Putting it all together

const { URL } = require('url'); // <------ This is new.

const Apify = require('apify');

Apify.main(async () => {

const requestQueue = await Apify.openRequestQueue();

await requestQueue.addRequest({ url: 'https://apify.com' });

const handlePageFunction = async ({ request, $ }) => {

const title = $('title').text();

console.log(`The title of "${request.url}" is: ${title}.`);

// Here starts the new part of handlePageFunction.

const links = $('a[href]')

.map((i, el) => $(el).attr('href'))

.get();

const { origin } = new URL(request.loadedUrl);

const absoluteUrls = links.map(

(link) => new URL(link, request.loadedUrl),

);

const sameDomainLinks = absoluteUrls.filter(

(url) => url.origin === origin,

);

console.log(`Enqueueing ${sameDomainLinks.length} URLs.`);

for (const url of sameDomainLinks) {

await requestQueue.addRequest({ url: url.href });

}

};

const crawler = new Apify.CheerioCrawler({

maxRequestsPerCrawl: 20, // <------ This is new too.

requestQueue,

handlePageFunction,

});

await crawler.run();

});

No matter if you followed along with our coding or just copy-pasted the resulting source, try running it now, perhaps even in both environments. You should see the crawler log the title of the first page, then the enqueueing message showing number of URLs, followed by the title of the first enqueued page and so on and so on.

If you need help with running the code, refer back to the chapters on environment setup: Setting up locally and Setting up on the Apify platform.

Using Apify SDK to enqueue links like a boss

If you were paying attention carefully in the previous chapter, we said that we would show you a way to enqueue new Requests with a single function

call. You might be wondering why we had to go through the whole process of getting the individual links, filtering the same domain ones and then

manually enqueuing them into the RequestQueue, when there is a simpler way.

Well, the obvious reason is practice. This is a tutorial after all. The other reason is to make you think about all the bits and pieces that come together, so that in the end, a new page, not previously entered in by you, can be scraped. We think that by seeing the bigger picture, you will be able to get the most out of Apify SDK.

Meet Apify.utils

We will talk at length about them later, but in short, Apify.utils is a namespace where you can find various helpful functions and constants that

make your life easier. One of the available functions is Apify.utils.enqueueLinks() which encapsulates the whole enqueueing process and even adds

some extra functionality.

Introduction to Apify.utils.enqueueLinks()

Since enqueuing new links to crawl is such an integral part of web crawling, we created a function that attempts to simplify this process as much as

possible. With a single function call, it allows you to find all the links on a page that match specified criteria and add them to a RequestQueue.

It also allows you to modify the resulting Requests to match your crawling needs.

enqueueLinks is quite a powerful function so, like crawlers, it gets its arguments from an options object. This is useful, because you don't have to

remember their order! But also because we can easily extend its API and add new features. You can

find the full reference here.

We suggest using ES6 destructuring to grab the enqueueLinks() function off of the utils object, so you don't have to type Apify.utils all the

time.

const Apify = require('apify');

const {

utils: { enqueueLinks },

} = Apify;

// Now you can use enqueueLinks like this:

await enqueueLinks({

/* options */

});

Basic use of enqueueLinks() with CheerioCrawler

We already implemented logic that takes care of enqueueing new links to a RequestQueue in the previous chapter on CheerioCrawler. Let's look at

that logic and implement the same functionality using enqueueLinks().

We found that the crawler needed to do these 4 things to crawl apify.com:

- Find new links on the page

- Filter only those pointing to

apify.com - Enqueue them to the

RequestQueue - Scrape the newly enqueued links

Using enqueueLinks() we can squash the first 3 into a single function call, if we set the options correctly. For now, let's just stick to the

basics. At the very least, we need a source where to find the links and the queue to enqueue them to. The $ Cheerio object is one of the sources the

function accepts and we already know how to work with it in the handlePageFunction. We also know how to get a requestQueue instance.

// Assuming previous existence of the '$' and 'requestQueue' variables.

await enqueueLinks({ $, requestQueue });

That's all we need to do to enqueue all <a href="..."> links from the given page to the given queue. Easy, right? Scratch number 1 and 3 off the

list. Only number 2 remains and to tackle this one, we need to talk about yet another new concept, the pseudo-URL.

Introduction to pseudo-URLs

Pseudo-URLs are represented by our PseudoUrl class and even though the name sounds discouraging, they're a pretty simple concept. They're just URLs

with some parts replaced by wildcards (read regular

expressions). They are matched against URLs to find specific links, domains, patterns, file extensions and so on.

In scraping, there are usually patterns to be found in website URLs that can be leveraged to scrape only the pages we're interested in. Imagine a typical online store. It has different categories which list different items The URL for might looks something like this:

https://www.online-store.com/categories

A category would then have a different URL:

https://www.online-store.com/categories/computers

Going to this page would produce a list of offered computers. Then, clicking on one of the computers might take us to a detail URL:

https://www.online-store.com/items/613804

As you can see, there's a structure to the links. In the real world, the structure might not always be perfectly obvious, but it's very often there. Pseudo-URLs help to use this structure to select only the relevant links from a given page.

Structure of a pseudo-URL

A pseudo-URL is a URL with regular expressions) enclosed

in [] brackets. Since we're running Node.js, the regular expressions should follow the JavaScript style.

For example, a pseudo-URL

https://www.online-store.com/categories/[(\w|-)+]

will match all of the following URLs:

https://www.online-store.com/categories/computers

https://www.online-store.com/categories/mobile-phones

https://www.online-store.com/categories/black-friday

but it will not match

https://www.online-store.com/categories

https://www.online-store.com/items/613804

This way, you can easily find just the URLs that you're looking for while ignoring the rest.

A pseudo-URL may include any number of bracketed regular expressions, so you can compose much more complex matching logic. The following Pseudo URL

will match the items in the store even if the links use the non-secure http protocol, omit the www from the hostname or use a different TLD.

http[s?]://[(www)?\.]online-store.[com|net|org]/items/[\d+]

will match any combination of:

http://www.online-store.org/items/12345

https://online-store.com/items/633423

http://online-store.net/items/7003

but it will not match:

http://shop.online-store.org/items/12345

https://www.online-store.com/items/calculator

www.online-store.org/items/7003

Pssst! Don't tell anyone, but you can create

PseudoUrlswith plain oldRegExpinstances instead of this brackety madness as well.

Using enqueueLinks() to filter links

That's been quite a lot of theory and examples. We might as well put it to practice. Going back to our CheerioCrawler exercise, we still have number

2 left to cross off the list - filter links pointing to apify.com. We've already shown that at the very least, the enqueueLinks() function needs

two arguments. The source, in our case the $ object, and the destination - the requestQueue. To filter links, we need to add a third argument:

pseudoUrls.

The options.pseudoUrls argument is always an Array, but its contents can take on many forms. See the reference

for all of them. Since we just need to filter out same domain links, we'll keep it simple and use a pseudo-URL string.

// Assuming previous existence of the '$' and 'requestQueue' variables.

const options = {

$,

requestQueue,

pseudoUrls: ['http[s?]://apify.com[.*]'],

};

await enqueueLinks(options);

To break the pseudo-URL string down, we're looking for both

httpandhttpsprotocols and the links may only lead toapify.comdomain. The final brackets[.*]allow everything, soapify.com/contactas well asapify.com/storewill match. If this sounds complex to you, we suggest reading a tutorial or two on regular expression syntax.

Resolving relative URLs with enqueueLinks()

TLDR; Just use baseUrl: request.loadedUrl when working with CheerioCrawler.

This is probably the weirdest and most complicated addition to the list. This is not the place to talk at length about absolute and relative paths, but in short, the links we encounter in a page can either be absolute, such as:

https://apify.com/john-doe/my-actor

or relative:

./john-doe/my-actor

Browsers handle this automatically, but since we're only using plain HTTP requests, we need to tell the enqueueLinks() function how to resolve the

relative links to the absolute ones, so we can use them for scraping. This is where the request.loadedUrl comes into play, because it returns the

correct URL to use as baseUrl.

// Assuming previous existence of the '$', 'requestQueue' and 'request' variables.

const options = {

$,

requestQueue,

pseudoUrls: ['http[s?]://apify.com[.*]'],

baseUrl: request.loadedUrl,

};

await enqueueLinks(options);

Even though it seems possible, we can't use the

request.urlof ourRequestinstances, because the page could have been redirected and the final URL would be different from the one we requested.

Integrating enqueueLinks() into our crawler

That was fairly easy, wasn't it. That ticks number 2 off our list and we're done! Let's take a look at the original crawler code, where we enqueued all the links manually.

const { URL } = require('url'); // <------ This is new.

const Apify = require('apify');

Apify.main(async () => {

const requestQueue = await Apify.openRequestQueue();

await requestQueue.addRequest({ url: 'https://apify.com' });

const handlePageFunction = async ({ request, $ }) => {

const title = $('title').text();

console.log(`The title of "${request.url}" is: ${title}.`);

// Here starts the new part of handlePageFunction.

const links = $('a[href]')

.map((i, el) => $(el).attr('href'))

.get();

const ourDomain = 'https://apify.com';

const absoluteUrls = links.map((link) => new URL(link, ourDomain));

const sameDomainLinks = absoluteUrls.filter((url) =>

url.href.startsWith(ourDomain),

);

console.log(`Enqueueing ${sameDomainLinks.length} URLs.`);

for (const url of sameDomainLinks) {

await requestQueue.addRequest({ url: url.href });

}

};

const crawler = new Apify.CheerioCrawler({

maxRequestsPerCrawl: 20, // <------ This is new too.

requestQueue,

handlePageFunction,

});

await crawler.run();

});

Since we've already prepared the enqueueLinks() options, we can just replace all the above enqueuing logic with a single function call, as promised.

const Apify = require('apify');

const {

utils: { enqueueLinks },

} = Apify;

Apify.main(async () => {

const requestQueue = await Apify.openRequestQueue();

await requestQueue.addRequest({ url: 'https://apify.com' });

const handlePageFunction = async ({ request, $ }) => {

const title = $('title').text();

console.log(`The title of "${request.url}" is: ${title}.`);

// Enqueue links

const enqueued = await enqueueLinks({

$,

requestQueue,

pseudoUrls: ['http[s?]://apify.com[.*]'],

baseUrl: request.loadedUrl,

});

console.log(`Enqueued ${enqueued.length} URLs.`);

};

const crawler = new Apify.CheerioCrawler({

maxRequestsPerCrawl: 20,

requestQueue,

handlePageFunction,

});

await crawler.run();

});

And that's it! No more parsing the links from HTML using Cheerio, filtering them and enqueueing them one by one It all gets done automatically!

enqueueLinks() is just one example of Apify SDK's powerful helper functions. They're all designed to make your life easier so you can focus on

getting your data, while leaving the mundane crawling management to your tools.

Apify.utils.enqueueLinks() has a lot more tricks up its sleeve. Make sure to check out the

reference documentation to see what else it can do for you. Namely the feature to prepopulate the Request

instances it creates with userData of your choice is extremely useful!

Getting some real-world data

Hey, guys, you know, it's cool that we can scrape the

<title>elements of web pages, but that's not very useful. Can we finally scrape some real data and save it somewhere in a machine readable format? Because that's why you started reading this tutorial in the first place!

We hear you, young padawan! First, learn how to crawl, you must. Only then, walk through data, you can!

### Making a store crawler

Fortunately, we don't have to travel to a galaxy far far away to find a good candidate for learning how to scrape

structured data. The Apify Store is a library of public actors that anyone can grab and use. You

can find ready-made solutions for crawling Google Places,

Amazon,

Google Search,

Booking,

Instagram,

Tripadvisor and many other websites. Feel free to check them out! It's also a great place to practice our Jedi scraping skills since it has categories, lists and details. That's almost like our imaginary

online-store.com from the previous chapter.

The importance of having a plan

Sometimes scraping is really straightforward, but most of the times, it really pays to do a little bit of research first. How is the website

structured? Can I scrape it only with HTTP requests (read "with CheerioCrawler") or would I need a full browser solution? Are there any

anti-scraping protections in place? Do I need to parse the HTML or can I get the data otherwise, such as directly from the website's API. Jakub,

one of Apify's founders, wrote a

great article about all the different techniques

and tips and tricks, so make sure to check that out!

For the purposes of this tutorial, let's just go ahead with HTTP requests and HTML parsing using CheerioCrawler. The number one reason being: We

already know how to use it and we want to build on that knowledge to learn specific crawling and scraping techniques.

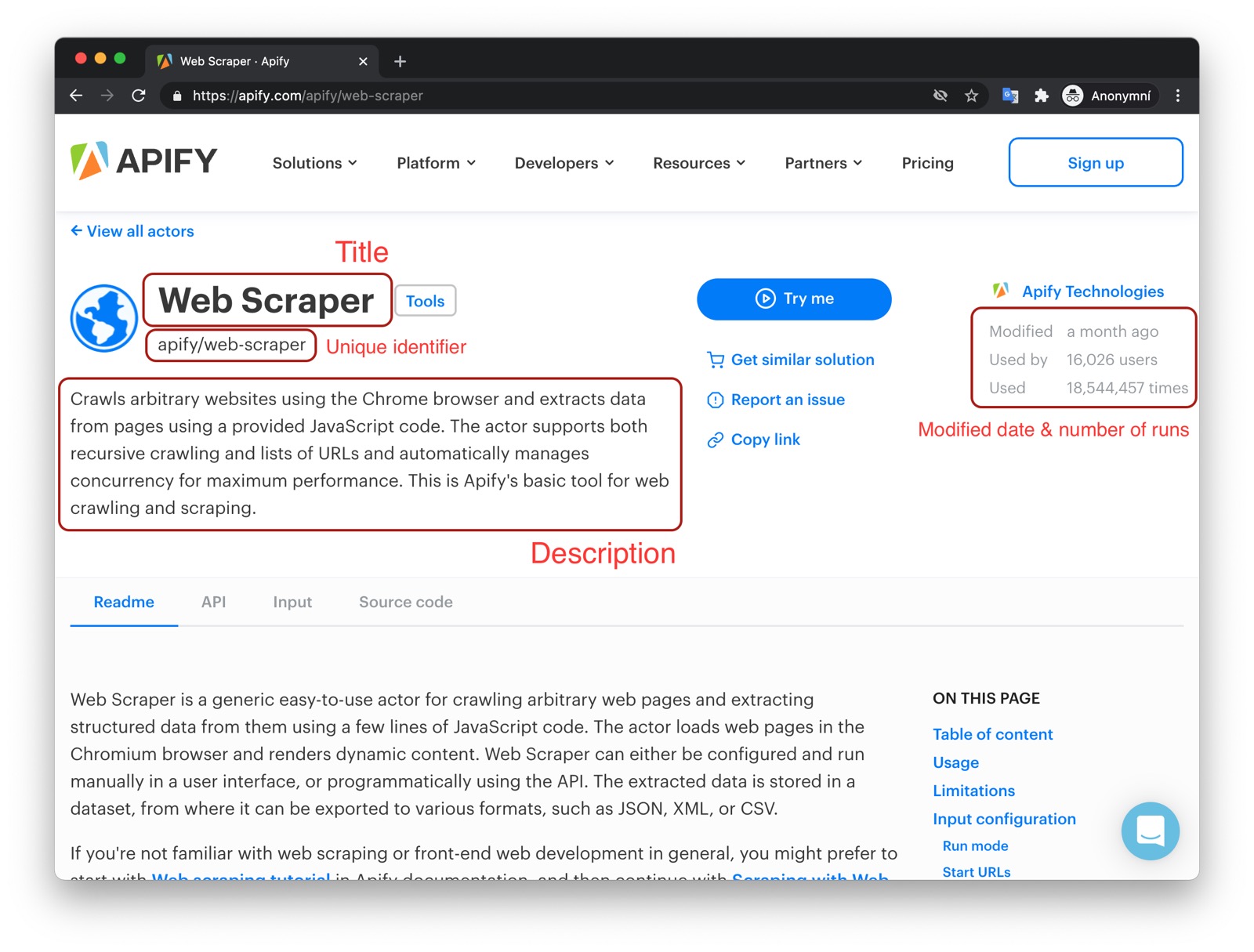

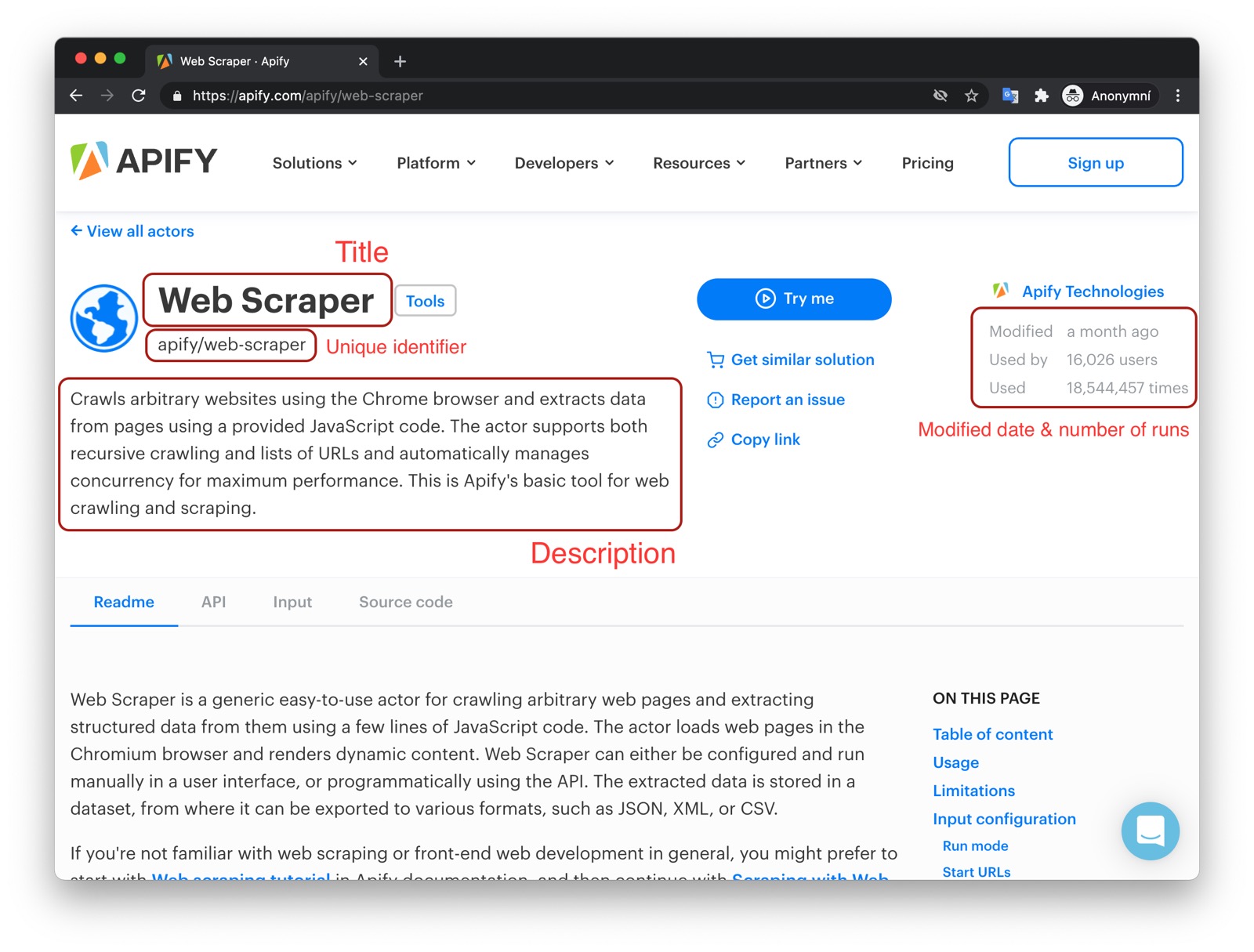

Choosing the data we need

A good first step is always to figure out what it is we want to scrape and where to find it. For the time being, let's just agree that we want to

scrape all actors (see the Show dropdown) in all categories (which can be found on the left side of the page) and for each actor we want to get its

- URL

- Owner

- Unique identifier (such as

apify/web-scraper) - Title

- Description

- Last modification date

- Number of runs

We can see that some of the information is available directly on the list page, but for details such as "Last modification date" or "Number of runs" we'll also need to open the actor detail pages.

Analyzing the target

Knowing that we will use plain HTTP requests, we immediately know that we won't be able to manipulate the website in any way. We will only be able to go through the HTML it gives us and parse our data from there. This might sound like a huge limitation, but you might be surprised in how effective it can be. Let's get to it!

The start URL(s)

This is where we start our crawl. It's convenient to start as close to our data as possible. For example, it wouldn't make much sense to start at

apify.com and look for a store link there, when we already know that everything we want to extract can be found at the apify.com/store page.

Once we look at the apify.com/store page more carefully, we see that the categories themselves produce URLs that we can use to access those

individual categories.

https://apify.com/store?category=ENTERTAINMENT

Should we write down all the category URLs down and use all of them as start URLs? It's definitely possible, but what if a new category appears on the page later? We would not learn about it unless we manually visit the page and inspect it again. So scraping the category links off the store page definitely makes sense. This way we always get an up to date list of categories.

But is it really that straightforward? By digging further into the store page's HTML we find that it does not actually contain the category links. The

menu on the left uses JavaScript to display the items from a given category and, as we've learned earlier, CheerioCrawler cannot execute JavaScript.

We've deliberately chosen this scenario to show an example of the number one weakness of

CheerioCrawler. We will overcome this difficulty in ourPuppeteerCrawlertutorial, but at the cost of compute resources and speed. Always remember that no tool is best for everything!

So we're back to the pre-selected list of URLs. Since we cannot scrape the list dynamically, we have to manually collect the links and then use them

in our crawler. We lose the ability to scrape new categories, but we keep the low resource consumption and speed advantages of CheerioCrawler.

Therefore, after careful consideration, we've determined that we should use multiple start URLs and that they should look as follows:

https://apify.com/store?category=TRAVEL

https://apify.com/store?category=ECOMMERCE

https://apify.com/store?category=ENTERTAINMENT

The crawling strategy

Now that we know where to start, we need to figure out where to go next. Since we've eliminated one level of crawling by selecting the categories manually, we now only need to crawl the actor detail pages. The algorithm therefore follows:

- Visit the category list page (one of our start URLs).

- Enqueue all links to actor details.

- Visit all actor details and extract data.

- Repeat 1 - 3 for all categories.

Technically, this is a depth first crawl and the crawler will perform a breadth first crawl by default, but that's an implementation detail. We've chosen this notation since a breadth first crawl would be less readable.

CheerioCrawler will make sure to visit the pages for us, if we provide the correct Requests and we already know how to enqueue pages, so this

should be fairly easy. Nevertheless, there are two more tricks that we'd like to show you.

Using a RequestList

RequestList is a perfect tool for scraping a pre-existing list of URLs and if you think about our start URLs, this is exactly what we have! A list

of links to the different categories of the store. Let's see how we'd get them into a RequestList.

const sources = [

'https://apify.com/store?category=TRAVEL',

'https://apify.com/store?category=ECOMMERCE',

'https://apify.com/store?category=ENTERTAINMENT',

];

const requestList = await Apify.openRequestList('categories', sources);

As you can see, similarly to the Apify.openRequestQueue() function, there is an Apify.openRequestList() function that will create a RequestList

instance for you. The first argument is the name of the RequestList. It is used to persist the crawling state of the list. This is useful when you

want to continue where you left off after an error or a process restart. The second argument is the sources array, which is nothing more than a list

of URLs you wish to crawl.

RequestQueueis a persistent store by default, so no name is needed, while theRequestListonly lives in memory and giving it a name enables it to become persistent.

You might now want to ask one of these questions:

- Can I enqueue into

RequestListtoo? - How do I make

RequestListwork together withRequestQueuesince I need the queue to enqueue newRequests.

The answer to the first one is a definitive no. RequestList is immutable and once you create it, you cannot add or remove Requests from it. The

answer to the second one is simple. RequestList and RequestQueue are made to work together out of the box in crawlers, so all you need to do is

use them both and the crawlers will do the rest.

const crawler = new Apify.CheerioCrawler({

requestList,

requestQueue,

handlePageFunction,

});

For those wondering how this works, the

RequestListRequestsare enqueued into theRequestQueueright before their execution and only processed by theRequestQueueafterwards. You can, of course, enqueue theRequeststo the queue manually, but that would take some boilerplate code and perhaps quite a long time, if we were talking about tens of thousands or moreRequests. The crawlers do it while running, so the time to enqueue is spread out and you won't even notice it.

#### Sanity check

It's always useful to create some simple boilerplate code to see that we've got everything set up correctly before we start to write the scraping logic itself. We might realize that something in our previous analysis doesn't quite add up, or the website might not behave exactly as we expected.

Let's use our newly acquired RequestList knowledge and everything we know from the previous chapters to create a new crawler that'll just visit all

the category URLs we selected and print the text content of all the actors in the category. Try running the code below in your selected environment.

You should see, albeit very badly formatted, the text of the individual actor cards that are displayed in the selected categories.

const Apify = require('apify');

Apify.main(async () => {

const sources = [

'https://apify.com/store?category=TRAVEL',

'https://apify.com/store?category=ECOMMERCE',

'https://apify.com/store?category=ENTERTAINMENT',

];

const requestList = await Apify.openRequestList('categories', sources);

const crawler = new Apify.CheerioCrawler({

requestList,

handlePageFunction: async ({ $, request }) => {

// Select all the actor cards.

$('.item').each((i, el) => {

const text = $(el).text();

console.log(`ITEM: ${text}\n`);

});

},

});

await crawler.run();

});

If there's anything you don't understand, refer to the previous chapters on setting up your environment, building your first crawler and

CheerioCrawler.

You might be wondering how we got that .item selector. After analyzing the category pages using a browser's DevTools, we've determined that it's a

good selector to select all the currently displayed actor cards. DevTools and CSS selectors are quite a large topic, so we can't go into too much

detail now, but here are a few general pointers.

DevTools crash course

We'll use Chrome DevTools here, since it's the most common browser, but feel free to use any other, it's all very similar.

We could pick any category, but let's just go with Travel because it includes some interesting actors. Go to

https://apify.com/store?category=TRAVEL

and open DevTools either by right-clicking anywhere in the page and selecting Inspect, or by pressing F12 or by any other means relevant to your

system. Once you're there, you'll see a bunch of DevToolsy stuff and a view of the category page with the individual actor cards.

Now, find the Select an element tool and use it to select one of the actor cards. Make sure to select the whole card, not just some of its contents, such

as its title or description.

In the resulting HTML display, it will put your cursor somewhere. Inspect the HTML around it. You'll see that there are CSS classes attached to the different HTML elements.

By hovering over the individual elements, you will see their placement in the page's view. It's easy to see the page's structure around the actor

cards now. All the cards are displayed in a <div> with a classname that starts with ItemsGrid__StyledDiv, which holds another <div> with some

computer-generated class names and finally, inside this <div>, the individual cards are represented by other <div> elements with the class of

item.

Yes, there are other HTML elements and other classes too. We can safely ignore them.

It should now make sense how we got that .item selector. It's just a selector that finds all elements that are annotated with the item class and

those just happen to be the actor cards only.

It's always a good idea to double check that though, so go into the DevTools Console and run

document.querySelectorAll('.item');

You will see that only the actor cards will be returned, and nothing else.

Enqueueing the detail links using a custom selector

In the previous chapter, we used the Apify.utils.enqueueLinks() function like this:

await enqueueLinks({

$,

requestQueue,

pseudoUrls: ['http[s?]://apify.com[.*]'],

baseUrl: request.loadedUrl,

});

While very useful in that scenario, we need something different now. Instead of finding all the <a href=".."> links that match the pseudoUrl, we

need to find only the specific ones that will take us to the actor detail pages. Otherwise, we'd be visiting a lot of other pages that we're not

interested in. Using the power of DevTools and yet another enqueueLinks() parameter, this becomes fairly easy.

const handlePageFunction = async ({ $, request }) => {

console.log(`Processing ${request.url}`);

// Only enqueue new links from the category pages.

if (!request.userData.detailPage) {

await Apify.utils.enqueueLinks({

$,

requestQueue,

selector: 'div.item > a',

baseUrl: request.loadedUrl,

transformRequestFunction: (req) => {

req.userData.detailPage = true;

return req;

},

});

}

};

The code should look pretty familiar to you. It's a very simple handlePageFunction where we log the currently processed URL to the console and

enqueue more links. But there are also a few new, interesting additions. Let's break it down.

The selector parameter of enqueueLinks()

When we previously used enqueueLinks(), we were not providing any selector parameter and it was fine, because we wanted to use the default

setting, which is a - finds all <a> elements. But now, we need to be more specific. There are multiple <a> links on the given category page, but

we're only interested in those that will take us to item (actor) details. Using the DevTools, we found out that we can select the links we wanted

using the div.item > a selector, which selects all the <a> elements that have a <div class="item ..."> parent. And those are exactly the ones

we're interested in.

The missing pseudoUrls

Earlier we learned that pseudoUrls are not required and if omitted, all links matching the given selector will be enqueued. This is exactly

what we need, so we're skipping pseudoUrls this time. That does not mean that you can't use pseudoUrls together with a custom selector though,

because you absolutely can!

Finally, the userData of enqueueLinks()

You will see userData used often throughout Apify SDK and it's nothing more than a place to store your own data on a Request instance. You can

access it with request.userData and it's a plain Object that can be used to store anything that needs to survive the full life-cycle of the

Request.

We can use the transformRequestFunction option of enqueueLinks() to modify all the Request instances it creates and enqueues. In our case, we

use it to set a detailPage property to the enqueued Requests to be able to easily differentiate between the category pages and the detail pages.

Another sanity check

It's always good to work step by step. We have this new enqueueing logic in place and since the previous Sanity check worked only

with a RequestList, because we were not enqueueing anything, don't forget to add back the RequestQueue and maxRequestsPerCrawl limit. Let's

test it out!

const Apify = require('apify');

Apify.main(async () => {

const sources = [

'https://apify.com/store?category=TRAVEL',

'https://apify.com/store?category=ECOMMERCE',

'https://apify.com/store?category=ENTERTAINMENT',

];

const requestList = await Apify.openRequestList('categories', sources);

const requestQueue = await Apify.openRequestQueue(); // <----------------

const crawler = new Apify.CheerioCrawler({

maxRequestsPerCrawl: 50, // <----------------------------------------

requestList,

requestQueue, // <---------------------------------------------------

handlePageFunction: async ({ $, request }) => {

console.log(`Processing ${request.url}`);

// Only enqueue new links from the category pages.

if (!request.userData.detailPage) {

await Apify.utils.enqueueLinks({

$,

requestQueue,

selector: 'div.item > a',

baseUrl: request.loadedUrl,

transformRequestFunction: (req) => {

req.userData.detailPage = true;

return req;

},

});

}

},

});

await crawler.run();

});

We've added the handlePageFunction() with the enqueueLinks() logic from the previous section to the code we wrote earlier. As always, try

running it in the environment of your choice. You should see the crawler output a number of links to the console, as it crawls the category pages first

and then all the links to the actor detail pages it found.

This concludes our Crawling strategy section, because we have taught the crawler to visit all the pages we need. Let's continue with scraping the tasty data.

Scraping data

At the beginning of this chapter, we created a list of the information we wanted to collect about the actors in the store. Let's review that and figure out ways to access it.

- URL

- Owner

- Unique identifier (such as

apify/web-scraper) - Title

- Description

- Last modification date

- Number of runs

Scraping the URL, Owner and Unique identifier

Some information is lying right there in front of us without even having to touch the actor detail pages. The URL we already have - the

request.url. And by looking at it carefully, we realize that it already includes the owner and the unique identifier too. We can just split the

string and be on our way then!

// request.url = https://apify.com/apify/web-scraper

const urlArr = request.url.split('/').slice(-2); // ['apify', 'web-scraper']

const uniqueIdentifier = urlArr.join('/'); // 'apify/web-scraper'

const owner = urlArr[0]; // 'apify'

It's always a matter of preference, whether to store this information separately in the resulting dataset, or not. Whoever uses the dataset can easily parse the

ownerfrom theURL, so should we duplicate the data unnecessarily? Our opinion is that unless the increased data consumption would be too large to bear, it's always better to make the dataset as readable as possible. Someone might want to filter byownerfor example and keeping only theURLin the dataset would make this complicated without using additional tools.

Scraping Title, Description, Last modification date and Number of runs

Now it's time to add more data to the results. Let's open one of the actor detail pages in the Store, for example the

apify/web-scraper page and use our DevTools-Fu to figure out how to get the title of the actor.

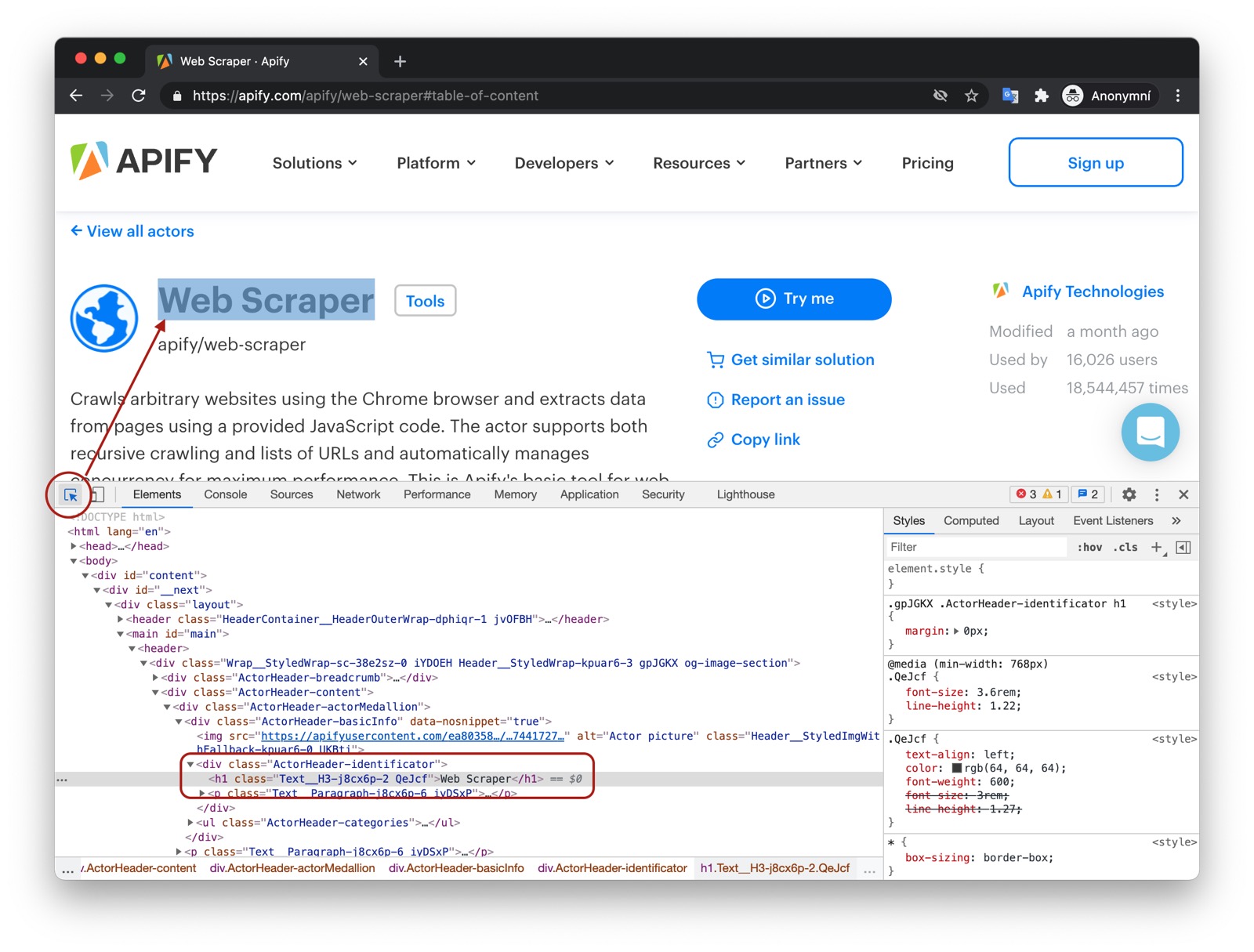

Title

By using the element selector tool, we find out that the title is there under an <h1> tag, as titles should be.

Maybe surprisingly, we find that there are actually two <h1> tags on the detail page. This should get us thinking.

Is there any parent element that includes our <h1> tag, but not the other ones? Yes, there is! There is a <header>

element that we can use to select only the heading we're interested in.

Remember that you can press CTRL+F (CMD+F) in the Elements tab of DevTools to open the search bar where you can quickly search for elements using their selectors. And always make sure to use the DevTools to verify your scraping process and assumptions. It's faster than changing the crawler code all the time.

To get the title we just need to find it using Cheerio and a header h1 selector, which selects all <h1> elements that have a <header> ancestor.

And as we already know, there's only one.

return {

title: $('header h1').text(),

};

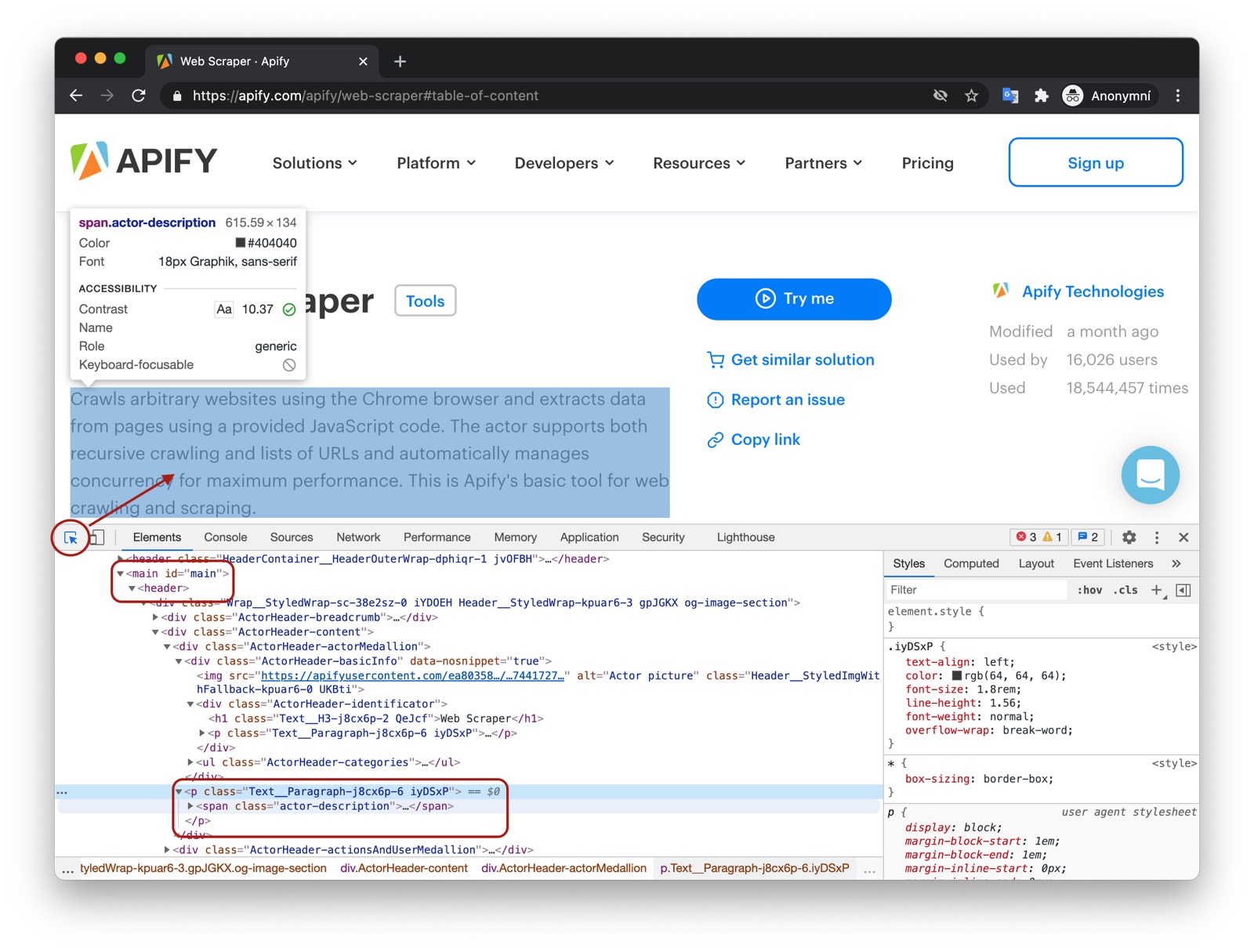

Description

Getting the actor's description is a little more involved, but still pretty straightforward. We can't just simply search for a <p> tag, because

there's a lot of them in the page. We need to narrow our search down a little. Using the DevTools we find that the actor description is nested within

the <header> element too, same as the title. Moreover, the actual description is nested inside a <span> tag with a class actor-description.

return {

title: $('header h1').text(),

description: $('header span.actor-description').text(),

};

Last modification date

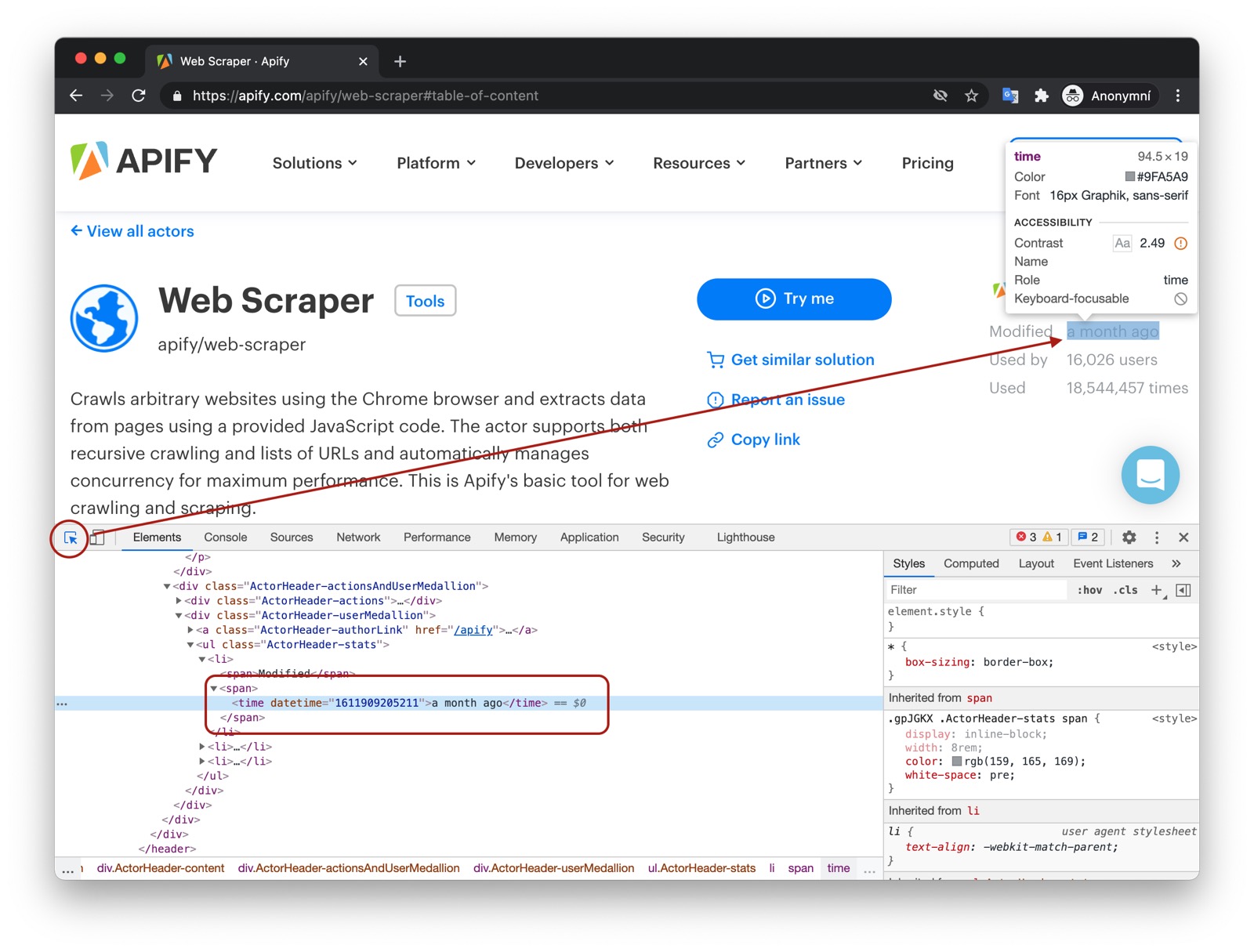

The DevTools tell us that the modifiedDate can be found in the <time> element inside <ul class="ActorHeader-stats">.

return {

title: $('header h1').text(),

description: $('header span.actor-description').text(),

modifiedDate: new Date(

Number($('ul.ActorHeader-stats time').attr('datetime')),

),

};

It might look a little too complex at first glance, but let's walk through it. We find the right <time> element,

and then we read its datetime attribute, because that's where a unix timestamp is stored as a string.

But we would much rather see a readable date in our results, not a unix timestamp, so we need to convert it. Unfortunately the new Date()

constructor will not accept a string, so we cast the string to a number using the Number() function before actually calling new Date().

Phew!

Run count

And so we're finishing up with the runCount. There's no specific element like <time>, so we need to create a complex selector and then do a

transformation on the result.

return {

title: $('header h1').text(),

description: $('header span.actor-description').text(),

modifiedDate: new Date(

Number($('ul.ActorHeader-stats time').attr('datetime')),

),

runCount: Number(

$('ul.ActorHeader-stats > li:nth-of-type(3)')

.text()

.match(/[\d,]+/)[0]

.replace(',', ''),

),

};

The ul.ActorHeader-stats > li:nth-of-type(3) looks complicated, but it only reads that we're looking for a <ul class="ActorHeader-stats ..."> element and within that

element we're looking for the third <li> element. We grab its text, but we're only interested in the number of runs. So we parse the number out

using a regular expression, but its type is still a string, so we finally convert the result to a number by wrapping it with a Number() call.

The numbers are formatted with commas as thousands separators (e.g.

'1,234,567'), so to extract it, we first use regular expression/[\d,]+/- it will search for consecutive number or comma characters. Then we extract the match via.match(/[\d,]+/)[0]and finally remove the commas by calling.replace(',', ''). This will give us a string (e.g.'1234567') that can be converted viaNumberfunction.

And there we have it! All the data we needed in a single object. For the sake of completeness, let's add the properties we parsed from the URL earlier and we're good to go.

const urlArr = request.url.split('/').slice(-2);

const results = {

url: request.url,

uniqueIdentifier: urlArr.join('/'),

owner: urlArr[0],

title: $('header h1').text(),

description: $('header span.actor-description').text(),

modifiedDate: new Date(

Number($('ul.ActorHeader-stats time').attr('datetime')),

),

runCount: Number(

$('ul.ActorHeader-stats > li:nth-of-type(3)')

.text()

.match(/[\d,]+/)[0]

.replace(',', ''),

),

};

console.log('RESULTS: ', results);

Trying it out (sanity check #3)

We have everything we need so just grab our newly created scraping logic, dump it into our original handlePageFunction() and see the magic happen!

const Apify = require('apify');

Apify.main(async () => {

const sources = [

'https://apify.com/store?category=TRAVEL',

'https://apify.com/store?category=ECOMMERCE',

'https://apify.com/store?category=ENTERTAINMENT',

];

const requestList = await Apify.openRequestList('categories', sources);

const requestQueue = await Apify.openRequestQueue();

const crawler = new Apify.CheerioCrawler({

maxRequestsPerCrawl: 50,

requestList,

requestQueue,

handlePageFunction: async ({ $, request }) => {

console.log(`Processing ${request.url}`);

// This is our new scraping logic.

if (request.userData.detailPage) {

const urlArr = request.url.split('/').slice(-2);

const results = {

url: request.url,

uniqueIdentifier: urlArr.join('/'),

owner: urlArr[0],

title: $('header h1').text(),

description: $('header span.actor-description').text(),

modifiedDate: new Date(

Number($('ul.ActorHeader-stats time').attr('datetime')),

),

runCount: Number(

$('ul.ActorHeader-stats > li:nth-of-type(3)')

.text()

.match(/[\d,]+/)[0]

.replace(',', ''),

),

};

console.log('RESULTS', results);

}

// Only enqueue new links from the category pages.

if (!request.userData.detailPage) {

await Apify.utils.enqueueLinks({

$,

requestQueue,

selector: 'div.item > a',

baseUrl: request.loadedUrl,

transformRequestFunction: (req) => {

req.userData.detailPage = true;

return req;

},

});

}

},

});

await crawler.run();

});

Notice again that we're scraping on the detail pages

request.userData.detailPage === true, but we're only enqueueing on the category pagesrequest.userData.detailPage === undefined.

When running the actor in the environment of your choice, you should see the crawled URLs and their scraped data printed to the console.

Saving the scraped data

A data extraction job would not be complete without saving the data for later use and processing. We've come to the final and most difficult part of this chapter so make sure to pay attention very carefully!

First, replace the console.log('RESULTS', results) call with

await Apify.pushData(results);

and that's it. Unlike in the previous paragraph, I'm being serious now. That's it, we're done. The final code therefore looks exactly like this:

const Apify = require('apify');

Apify.main(async () => {

const sources = [

'https://apify.com/store?category=TRAVEL',

'https://apify.com/store?category=ECOMMERCE',

'https://apify.com/store?category=ENTERTAINMENT',

];

const requestList = await Apify.openRequestList('categories', sources);

const requestQueue = await Apify.openRequestQueue();

const crawler = new Apify.CheerioCrawler({

maxRequestsPerCrawl: 50,

requestList,

requestQueue,

handlePageFunction: async ({ $, request }) => {

console.log(`Processing ${request.url}`);

// This is our new scraping logic.

if (request.userData.detailPage) {

const urlArr = request.url.split('/').slice(-2);

const results = {

url: request.url,

uniqueIdentifier: urlArr.join('/'),

owner: urlArr[0],

title: $('header h1').text(),

description: $('header span.actor-description').text(),

modifiedDate: new Date(

Number($('ul.ActorHeader-stats time').attr('datetime')),

),

runCount: Number(

$('ul.ActorHeader-stats > li:nth-of-type(3)')

.text()

.match(/[\d,]+/)[0]

.replace(',', ''),

),

};

await Apify.pushData(results);

}

// Only enqueue new links from the category pages.

if (!request.userData.detailPage) {

await Apify.utils.enqueueLinks({

$,

requestQueue,

selector: 'div.item > a',

baseUrl: request.loadedUrl,

transformRequestFunction: (req) => {

req.userData.detailPage = true;

return req;

},

});

}

},

});

await crawler.run();

});

What's Apify.pushData()

Apify.pushData() is a helper function that saves data to the default Dataset. Dataset is a

storage designed to hold virtually unlimited amount of data in a format similar to a table. Each time you call Apify.pushData() a new row in the

table is created, with the property names serving as column titles.

Each actor run has one default

Datasetso no need to initialize it or create an instance first. It just gets done automatically for you. You can also create named datasets at will.

Finding my saved data

It might not be perfectly obvious where the data we saved using the previous command went, so let's break it down by environment:

Dataset on the Apify platform

Open any Run of your actor on the Platform and you will see a Dataset as one of the available tabs. Clicking on it will reveal basic information about the Dataset and a list of options that you can use to download your data. There are various formats such as JSON, XLSX or CSV available and there's also the possibility of downloading only clean items, i.e. a filtered dataset with empty rows and hidden fields removed.

Local Dataset

Unless you changed the environment variables that Apify SDK uses locally, which would suggest that you knew what you were doing and you didn't need this tutorial anyway, you'll find your data in your local Apify Storage.

{PROJECT_FOLDER}/apify_storage/datasets/default/

The above folder will hold all your saved data in numbered files, as they were pushed into the dataset. Each file represents one invocation of

Apify.pushData() or one table row.

Unfortunately, the local datasets don't yet support the export in various formats functionality that the Platform Dataset page offers, so for the time being, we're stuck with JSON.

Final touch

It may seem that the data are extracted and the actor is done, but honestly, this is just the beginning. For the sake of brevity, we've completely omitted error handling, proxies, debug logging, tests, documentation and other stuff that a reliable software should have. The good thing is, error handling is mostly done by Apify SDK itself, so no worries on that front, unless you need some custom magic.

Anyway, to spark some ideas, let's look at two more things. First, passing an input to the actor, which will enable us to change the categories we want to scrape without changing the source code itself! And then some refactoring, to show you how we reckon is preferable to structure and annotate actor code.

Meet the INPUT

INPUT is just a convention on how we call the actor's input. Because there's no magic in actors, just features, the INPUT is actually nothing more

than a key in the default KeyValueStore that's, by convention, used as input on the Apify platform. Also by convention, the

INPUT is mostly expected to be of Content-Type: application/json.

We will not go into KeyValueStore details here, but for the sake of INPUT you need to remember that there is a function that helps you get it.

const input = await Apify.getInput();

On the Apify Platform, the actor's input that you can set in the Console is automatically saved to the default KeyValueStore under the key INPUT

and by calling Apify.getInput() you retrieve the value from the KeyValueStore.

Running locally, you need to place an INPUT.json file in your default key value store for this to work.

{PROJECT_FOLDER}/apify_storage/key_value_stores/default/INPUT.json

Use INPUT to seed our actor with categories

Currently we're using the full URLs of categories as sources, but it's quite obvious that we only need the final parameters, the rest of the URL is

always the same. Knowing that, we can pass an array of those parameters on INPUT and build the URLs dynamically, which would allow us to scrape

different categories without changing the source code. Let's get to it!

First, we set up our INPUT, either in the INPUT form of the actor on the Apify platform, or by creating an INPUT.json in our default key-value store

locally.

["TRAVEL", "ECOMMERCE", "ENTERTAINMENT"]

Once we have that, we can load it in the actor and populate the crawler's sources with it. In the following example, we're using the categories in the

input to construct the category URLs and we're also passing custom userData to the sources. This means that the Requests that get created will

automatically contain this userData.

// ...

const input = await Apify.getInput();

const sources = input.map((category) => ({

url: `https://apify.com/store?category=${category}`,

userData: {

label: 'CATEGORY',

},

}));

const requestList = await Apify.openRequestList('categories', sources);

// ...

The userData.label is also a convention that we've been using for quite some time to label different Requests. We know that this is a category URL

so we label it CATEGORY. This way, we can easily make decisions in the handlePageFunction without having to inspect the URL itself.

We can then refactor the if clauses in the handlePageFunction to use the label for decision-making. This does not make much sense for a crawler

with only two different pages, because a simple boolean would suffice, but for pages with multiple different views, it becomes very useful.

Structuring the code better

But perhaps we should not stop at refactoring the if clauses. There are several ways we can make the actor look more elegant and - most

importantly - easier to reason about and make changes to.

In the following code we've made several changes.

- Split the code into multiple files.

- Added the

Apify.utils.logand replacedconsole.logwith it. - Added a

getSources()function to encapsulateINPUTconsumption. - Added a

createRouter()function to make our routing cleaner, without nestedifclauses. - Removed the

maxRequestsPerCrawllimit.

To create a multi-file actor on the Apify Platform, select Multiple source files in the Type dropdown on the Source screen.

In our main.js file, we place the general structure of the crawler:

// main.js

const Apify = require('apify');

const tools = require('./tools');

const {

utils: { log },

} = Apify;

Apify.main(async () => {

log.info('Starting actor.');

const requestList = await Apify.openRequestList(

'categories',

await tools.getSources(),

);

const requestQueue = await Apify.openRequestQueue();

const router = tools.createRouter({ requestQueue });

log.debug('Setting up crawler.');

const crawler = new Apify.CheerioCrawler({

requestList,

requestQueue,

handlePageFunction: async (context) => {

const { request } = context;

log.info(`Processing ${request.url}`);

await router(request.userData.label, context);

},

});

log.info('Starting the crawl.');

await crawler.run();

log.info('Actor finished.');

});

Then in a separate tools.js, we add our helper functions:

// tools.js

const Apify = require('apify');

const routes = require('./routes');

const {

utils: { log },

} = Apify;

exports.getSources = async () => {

log.debug('Getting sources.');

const input = await Apify.getInput();

return input.map((category) => ({

url: `https://apify.com/store?category=${category}`,

userData: {

label: 'CATEGORY',

},

}));

};

exports.createRouter = (globalContext) => {

return async function (routeName, requestContext) {

const route = routes[routeName];

if (!route) throw new Error(`No route for name: ${routeName}`);

log.debug(`Invoking route: ${routeName}`);

return route(requestContext, globalContext);

};

};

And finally our routes in a separate routes.js file:

// routes.js

const Apify = require('apify');

const {

utils: { log },

} = Apify;

exports.CATEGORY = async ({ $, request }, { requestQueue }) => {

return Apify.utils.enqueueLinks({

$,

requestQueue,

selector: 'div.item > a',

baseUrl: request.loadedUrl,

transformRequestFunction: (req) => {

req.userData.label = 'DETAIL';

return req;

},

});

};

exports.DETAIL = async ({ $, request }) => {

const urlArr = request.url.split('/').slice(-2);

log.debug('Scraping results.');

const results = {

url: request.url,

uniqueIdentifier: urlArr.join('/'),

owner: urlArr[0],

title: $('header h1').text(),

description: $('header span.actor-description').text(),

modifiedDate: new Date(

Number($('ul.ActorHeader-stats time').attr('datetime')),

),

runCount: Number(

$('ul.ActorHeader-stats > li:nth-of-type(3)')

.text()

.match(/[\d,]+/)[0]

.replace(',', ''),

),

};

log.debug('Pushing data to dataset.');

await Apify.pushData(results);

};

Let us tell you a little bit more about the changes. We hope that in the end, you'll agree that this structure makes the actor more readable and manageable.

Splitting your code into multiple files

This was not always the case, but now that the Apify platform has a multifile editor, there's no reason not to split your code into multiple files and keep your logic separate. Less code in a single file means less code you need to think about at any time, and that's a great thing!

Using Apify.utils.log instead of console.log

We wont go to great lengths here to talk about utils.log, because you can read it all in the documentation, but there's just

one thing that we need to stress: log levels.

utils.log enables you to use different log levels, such as log.debug, log.info or log.warning. It not only makes your log more readable, but

it also allows selective turning off of some levels by either calling the utils.log.setLevel() function or by setting an APIFY_LOG_LEVEL variable.

This is huge! Because you can now add a lot of debug logs in your actor, which will help you when something goes wrong and turn them on or off with a

simple INPUT change, or by setting an environment variable.

The punch line? Use Apify.utils.log instead of console.log now and thank us later when something goes wrong!

Using a router to structure your crawling

At first, it might seem more readable using just a simple if / else statement to select different logic based on the crawled pages, but trust me, it

becomes far less impressive when working with more than two different pages and it definitely starts to fall apart when the logic to handle each page

spans tens or hundreds of lines of code.

It's good practice in any programming to split your logic into bite-sized chunks that are easy to read and reason about. Scrolling through a

thousand line long handlePageFunction() where everything interacts with everything and variables can be used everywhere is not a beautiful thing to

do and a pain to debug. That's why we prefer the separation of routes into a special file and with large routes, we would even suggest having one file

per route.

TO BE CONTINUED with details on

PuppeteerCrawlerand other features...