Type aliases

Create your own custom types using the "type" keyword, understand the "void" type, and learn how to write custom function types.

Real quick, let's look at this code:

// Using a union type to allow value to be either a string,

// a number, or a boolean

const returnValueAsString = (value: string | number | boolean) => {

return `${value}`;

};

let myValue: string | number | boolean;

myValue = 55;

console.log(returnValueAsString(myValue));

This is fine, but we had to write string | number | boolean twice, and if this were a large project, we'd likely find ourselves writing it even more times. The solution for this is to define the type elsewhere, giving it a name by which it can be identified, and then to use that name within the type annotations for returnValueAsString and myValue.

Creating types

With the type keyword, you can abstract all the type stuff you'd normally put in a type annotation into one type alias. The great thing about type aliases is that they improve code readability and can be used in multiple places.

First, we'll use the type keyword and call the type MyUnionType.

type MyUnionType = any;

Then, we can just copy-paste the union type between a string, number, and boolean and paste it after the equals sign:

type MyUnionType = string | number | boolean;

The type is now stored under this MyUnionType alias.

Any type declaration "logic" that you can place within a type annotation can also be stored under a type alias.

Using type aliases

All we need to do to refactor the code from the beginning of the lesson is replace the type annotations with MyUnionType:

type MyUnionType = string | number | boolean;

const returnValueAsString = (value: MyUnionType) => {

return `${value}`;

};

let myValue: MyUnionType;

myValue = 55;

console.log(returnValueAsString(myValue));

Function types

Before we learn about how to write function types, let's learn about a problem they can solve. We have a function called addAll which takes in array of numbers, adds them all up, and then returns the result.

const addAll = (nums: number[]) => {

return nums.reduce((prev, curr) => prev + curr, 0);

};

We want to add the ability to choose whether or not the result should be printed to the console. A function's parameter can be marked as optional by using a question mark.

Let's do that now.

// We've added a return type to the function because it will return different

// things based on the "printResult" parameter. When false, a number will be

// returned, while when true, nothing will be returned (void).

const addAll = (nums: number[], printResult?: boolean): number | void => {

const result = nums.reduce((prev, curr) => prev + curr, 0);

if (!printResult) return result;

console.log('Result:', result);

};

Also, it'd be nice to have some option to pass in a custom message for when the result is logged to the console, so we'll add another optional parameter for that.

const addAll = (nums: number[], printResult?: boolean, printWithMessage?: string): number | void => {

const result = nums.reduce((prev, curr) => prev + curr, 0);

if (!printResult) return result;

console.log(printWithMessage || 'Result:', result);

};

Finally, we'll add a final parameter with the option to return/print the result as a string instead of a number.

const addAll = (nums: number[], toString?: boolean, printResult?: boolean, printWithMessage?: string): number | string | void => {

const result = nums.reduce((prev, curr) => prev + curr, 0);

if (!printResult) return toString ? result.toString() : result;

console.log(printWithMessage || 'Result:', toString ? result.toString : result);

};

What we're left with is a massive function declaration that is very verbose. This isn't necessarily a bad thing, but all of these typings could be put into a function type instead.

Creating & using function types

Function types are declared with the type keyword (or directly within a type annotation), and are written in a similar fashion to regular arrow functions. All parameters and their types go inside the parentheses (()), and the return type of the function goes after the arrow (=>).

type AddFunction = (numbers: number[], toString?: boolean, printResult?: boolean, printWithMessage?: string) => number | string | void;

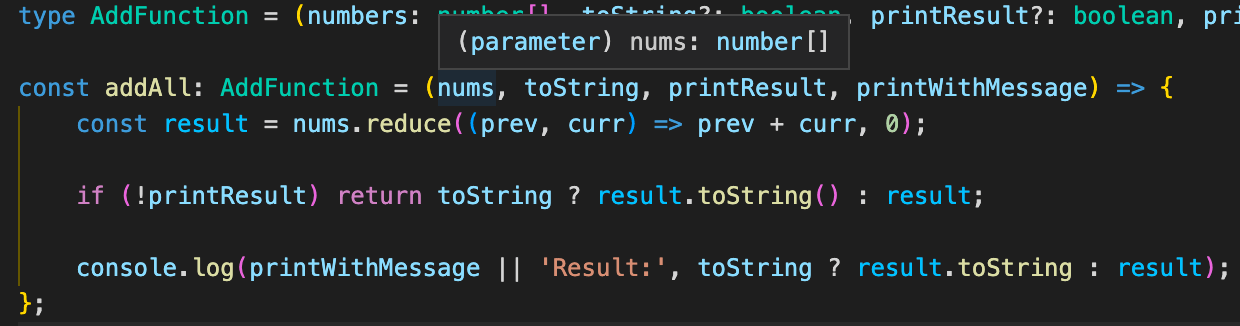

This is where the true magic happens. Because our arrow function is stored in a variable, and because we've now created the AddFunction type, we can delete all type annotations from the function itself and annotate the variable with AddFunction instead.

type AddFunction = (numbers: number[], toString?: boolean, printResult?: boolean, printWithMessage?: string) => number | string | void;

const addAll: AddFunction = (nums, toString, printResult, printWithMessage) => {

const result = nums.reduce((prev, curr) => prev + curr, 0);

if (!printResult) return toString ? result.toString() : result;

console.log(printWithMessage || 'Result:', toString ? result.toString : result);

};

We've significantly cleaned up the function by moving its verbose type annotations into a type alias without losing the benefits of TypeScript.

Next up

A special type exists that you haven't learned about yet called unknown. We haven't yet discussed it, because it's best learned alongside type casting, which is yet another feature offered by TypeScript. Learn all about the unknown type and typecasting in the next lesson.